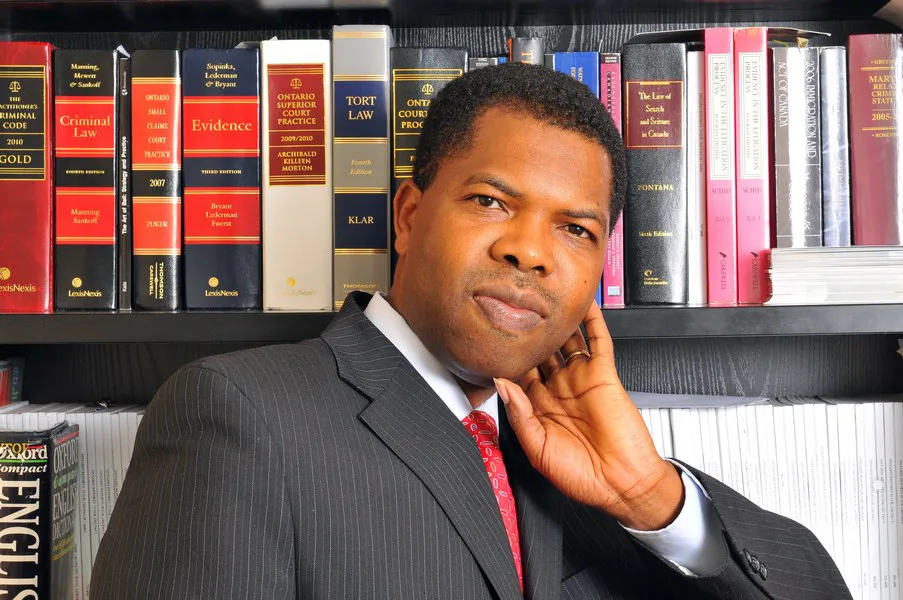

Johnson Babalola

Every time I visit Nigeria and step into a bank—whether to transact business or accompany someone—I am struck, almost unsettled, by how banking is conducted. Perhaps those with access to private banking, personal managers, or “connections” may not fully grasp what I am about to describe. This reality is often invisible to them.

It begins even before you enter the building. Parking is a battle. One wonders whether regulatory authorities ever considered the relationship between bank approvals, expected foot traffic, and parking capacity. If you eventually find a space, navigating into it without damaging another vehicle feels like a test of professional driving skill.

Once parked, the ritual begins. A security officer—who may or may not have helped you—greets you warmly, expectantly. Polite exchanges follow, layered with unspoken social obligations. At the entrance, another security officer rushes to press the access button for you, offers blessings, directs how you should hold your phone, and locks eyes in a way that silently communicates expectation. You are still outside the bank, yet already navigating human pressure.

Then you enter the banking hall.

It feels less like a financial institution and more like a crowded open market. There is noise, confusion, overlapping conversations. You ask where to queue, and a stranger assures you that you are “at the right place.” You join the line and soon realize that privacy is entirely absent.

Sensitive information is exchanged openly.

“Mama, what is your BVN?” a staff member asks loudly.

An elderly woman responds just as loudly, reciting the numbers.

Nearby, another conversation unfolds:

“How much do you want to withdraw?”

“One million naira.”

“We can only give you one hundred thousand.”

Voices rise. Frustration spills into the open. Soon, a supervisor intervenes, offering a compromise. Everyone hears everything—amounts, names, needs, vulnerabilities. Nothing is private. Nothing is discreet.

When it is finally your turn, you expect one-on-one service. Instead, the teller is attending to multiple customers simultaneously. An elderly man walks up, greets the teller by name, and a long personal conversation begins—right there, in front of everyone. Another customer asks for help filling a withdrawal form. A young lady behind you struggles to be heard. Then comes the familiar announcement: “The system is down.”

As we wait, I reflect on a friend’s advice: “JB, why do you still go to banks? There are other ways.” Perhaps he is right. But perhaps he misses the point. Each visit to the bank is a lesson—a window into society.

I see people queue to withdraw ₦1,000.

I see people treated differently based on status, appearance, or familiarity.

I see customer service that is transactional and expectant, not respectful.

Most troubling, I see how disconnected leadership can become from everyday realities. Those who make decisions rarely stand in these lines. They do not hear these conversations. They do not witness these vulnerabilities. Like many leaders, they remain far removed—from banks, hospitals, markets, schools, and bus stops—places where the true condition of society is visible.

After about fifteen minutes, the system comes back up. But what stayed with me most was not the delay. It was the glaring absence of privacy and confidentiality.

Bank staff routinely request sensitive personal and financial information loudly, in open spaces. Customers—many uneducated or unfamiliar with banking processes—depend on complete strangers in the hall to help them fill forms or navigate procedures. There are no meaningful safeguards. No quiet spaces. No sense of confidentiality.

Most troubling, I see how disconnected leadership can become from everyday realities. Those who make decisions rarely stand in these lines. They do not hear these conversations. They do not witness these vulnerabilities. Like many leaders, they remain far removed—from banks, hospitals, markets, schools, and bus stops—places where the true condition of society is visible.

As I exited the hall, I witnessed what felt like the final indictment: an elderly woman handing her ATM PIN to a security officer to help her reset it.

I shook my head.

Outside, the same security officer from earlier reappeared, offering blessings again. I smiled back, aware that he too is only trying to survive. As I sat in the car and drove off, one question lingered in my mind:

Why are we surprised when accounts are hacked, funds disappear, and trust in the banking system erodes—when privacy and confidentiality are treated as optional, not fundamental?

Until Nigerian banking culture takes privacy seriously—not as a luxury, but as a right—the system will continue to expose the very people it is meant to protect.

Johnson Babalola (JB) is a Canadian lawyer

@jbdlaw